According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Globally, one in every 122 humans is now either a refugee, internally displaced, or seeking asylum. If this were the population of a country, it would be the world’s 24th biggest.” This quote represents over 59 million displaced people across the globe.

Refugee movements are an inherent part of international politics as their consequences, causes, and responses are intertwined with state actions, as forced migration has an inextricable relationship with conflict. Across many countries, newfound border tightening measures harm refugees’ ability to seek asylum, as they are forced into squalor and/or refugee camps. The UNHCR is the international organization dedicated to protecting refugees internationally and focuses on durable solutions to improve refugee situations. There are three main solutions towards refugee situations: temporary asylum (where refugees are integrated into local areas), third-county resettlement (where refugees immigrate and acclimate to a new country), and voluntary repatriation (where refugees return to their country of origin).

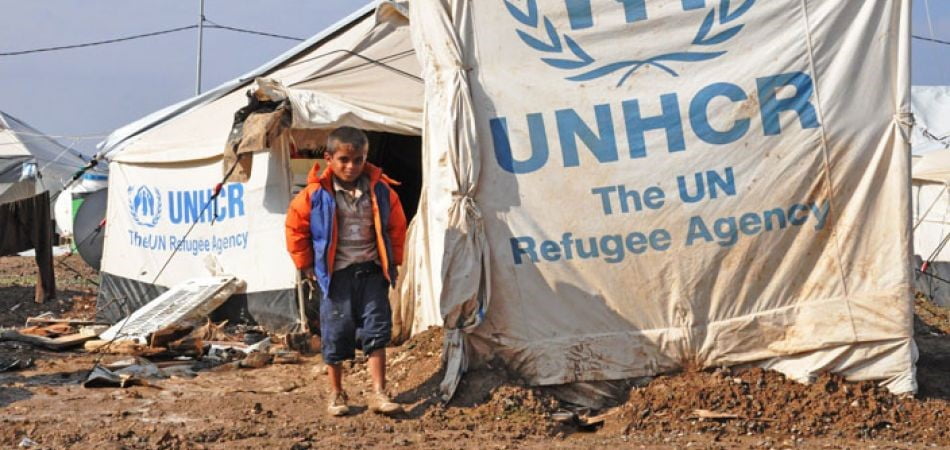

Temporary asylum is mainly practiced today as the administration of refugee camps in border countries to the main conflict. These camps are largely underfunded, which places a massive strain on the host government to provide the land and other resources for protection. Many refugees stay in camps of their neighboring countries without local integration for a decade or more before they get a chance to resettle in a third country. Refugee camps are unsustainable quasi-solutions but attract international donors because their aid impact is more readily seen. They are unsustainable because they do not allow refugees to become self-reliant, and their continual dependence on services from the camp will exacerbate the conflict, as they do not gain transferable skills to help rebuild their home societies or third country resettlement whenever they are able to return.

The UNHCR has championed repatriation as the main method to solve refugee migrations. The underlying assumption of repatriation is that refugees will voluntarily return to their home countries once the violence that they fled from subsides. This assumption is problematic because it overlooks the direct needs of the refugees as well as creates a policy where international organizations like the UNHCR can enforce repatriation due to the relatively safer home country conditions than before the refugees left, even if this means the overall violence has not ended. Through continually championing repatriation, the UNHCR was able to normalize this solution to refugee crises.

If there were more international motivation to resolve home country conflicts, then voluntary repatriation would be a stronger durable solution. If there were more funding for integrating refugees into local host country economies, then temporary asylum would be a stronger durable solution. Because neither of these scenarios reflects modern international politics, third-country resettlement must become a more dominant solution. However, states are not obliged to accept refugees for resettlement but rather voluntarily offer accommodation as a tangible expression of international solidarity. Third-country resettlement can only be achieved through collaboration with various resettlement states, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs,) but resettlement must be a complement to, and not a substitute for, the provision of international protection for those that apply for asylum status.