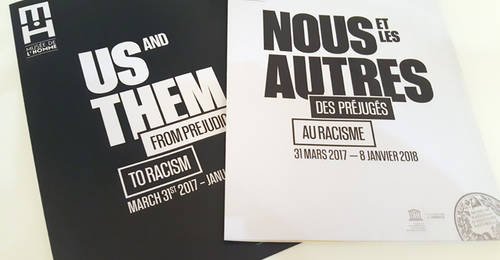

Musée de l’Homme, Paris, France, 31 March 2017 – 8 January 2018

- Me and them

We are all members of the great family of humankind, but each of us is unique, heir to our history but also author of our own life. Our physical appearance, our cultural practices, our religious beliefs, our geographical origins and our position in society are all characteristics – just points on an infinite spectrum – that differentiate us from one another.Our identity therefore comprises many different components, and we should all be free to highlight whichever ones we choose. However, certain historical, social or political contexts have defined certain traits as differences, and used these to imprison individuals in readymade representations and to divide them into categories. The resulting stereotypes and prejudice, whether conscious or unconscious, tend to favour people like us at the risk of discriminating against everyone who isn’t. And as soon as these “differences” are organized into a hierarchy and essentialized, is alive and thrives…

The first part of the exhibition invites us to discover how identity and alterity are forged, and understand the processes of categorization, hierarchization and essentialization that partake in the production of “everyday” racism. - Race and history

There were two specific contexts in which institutional racism flourished in the West’s sphere of influence between the 16th and 20th centuries – colonial rule, and nationalism.From the 16th to the 18th century, slavery fostered the categorization of people into different kinds amid a prevailing, colonization-induced climate of violence and domination. This phenomenon was given a new lease of life in the 19th century as the major European powers colonized new territories.

The geopolitical situation influenced scholars in their attempts to use the concept of “race” to classify the many diverse types of human being. Categorization morphed into racialization and eventually developed into “institutional racism”. Racial segregation in the United States had its roots in the racialization that emerged during slavery.

Nationalism was a second vector of racism. In the 20th century the Nazis pushed their obsession with racial purity to its most horrifying conclusion – genocide. Rwanda was an emblematic case, because it combined the two principal vectors of racialization: colonialism, which laid the groundwork for the phenomenon, and nationalism, which rekindled it. Racism is not restricted to European countries and their colonies, since it also exists, or used to exist, in other cultures. - The situation today

Today’s political and intellectual environment is very different from the one that fostered the rise of institutional racism. The General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The French state has stepped up its efforts to combat racism since the 1970s. Although social scientists have shown that diversity is generally tolerated by the majority population, and that second-generation immigrants have integrated well, certain minority groups still suffer noticeably from unequal treatment and discrimination.

We have to admit the failure of anti-racist campaigns between the 1960s and the 1980s, based on scientific research disproving the existence of several “human races”. A multidisciplinary approach between researchers in the life sciences, the humanities and the social sciences has now analyzed the racialist mechanisms operating in racist speeches and practices, and warns against them. Underpinning this approach is a reassertion of the principle that all humans are equal.